Unlivable

The 2025 United Way ALICE report shows that half of households in the greater Florence area earn below a livable income

Written and photographed

by Will Yurman

Shana Marie Simpson woke up around 8 a.m., tired, cold and stiff. She stretched as best she could, folded her sleeping bag and climbed out of bed – the back seat of her 2004 silver VW Passat.

It was late November 2024, just a few days before Thanksgiving. Simpson had been living out of her car since moving to Florence in September. In some ways, things were looking up. She had a job at Safeway and was getting good hours, and moving to Florence meant she was close to her dad.

But she was struggling to find an apartment she could afford, and the car had a broken CV joint and a leak somewhere that was letting in the rain. And she didn’t have the gas money to get to Eugene, where she knew someone who would help her fix it.

ALICE

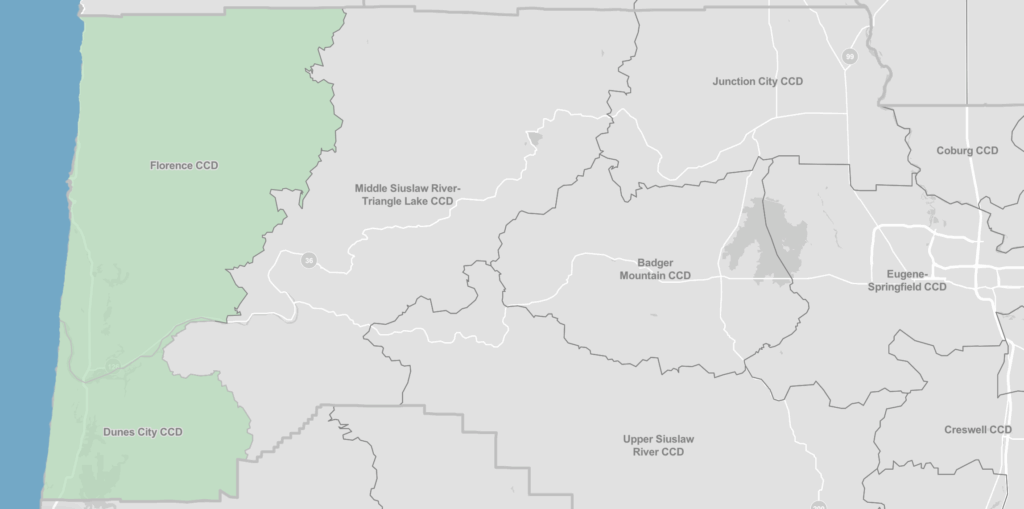

Half, 50%, one in two households in and around Florence, from Mapleton to Dunes City, earn below a livable wage. It is an antiseptic way of describing how many families struggle each month to pay for a place to live, and for food, clothes, medicine, gas for their cars, and childcare for their kids.

The number comes from the United Way’s most recent ALICE report, using data from 2023 (the most recent complete data set available). By comparison, 42% of Oregon households and American households nationally earn below a sustainable income, according to the report.

SHANA

Shana Marie Simpson is 44. She was born in Grants Pass but has lived all over the country. She is a single mom with two twenty-something sons. In 2007, they were living in the Eugene-Springfield area. It was a period of some stability and comfort following a bitter breakup from her sons’ father. “While I was in Eugene, I built friendships and focused on counseling and therapy. I focused on healing myself and building myself up and healing and helping my sons heal,” she said.

She held multiple jobs, often at the same time, as a cashier, a cook, a house cleaner, and a farmhand, all while raising her kids. It was ten years of relative financial security.

In April 2018, she woke up to a bright light in their second-floor townhouse apartment in Springfield. Then she heard the roar. It grew louder, fully waking her, and she realized the building was on fire. She woke the boys and they grabbed the dog. A neighbor helped them climb out a window. “We all just stood and watched my house burn, and everything in it,” Simpson said.

It burned Simpson’s possessions and would also burn through her savings, leaving the family with few options for affordable housing in Eugene or Springfield.

ALICE

ALICE is a slightly strained acronym for Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed. It’s about people, measured by households, who are working, but with wages that don’t keep up with the cost of living—the working poor.

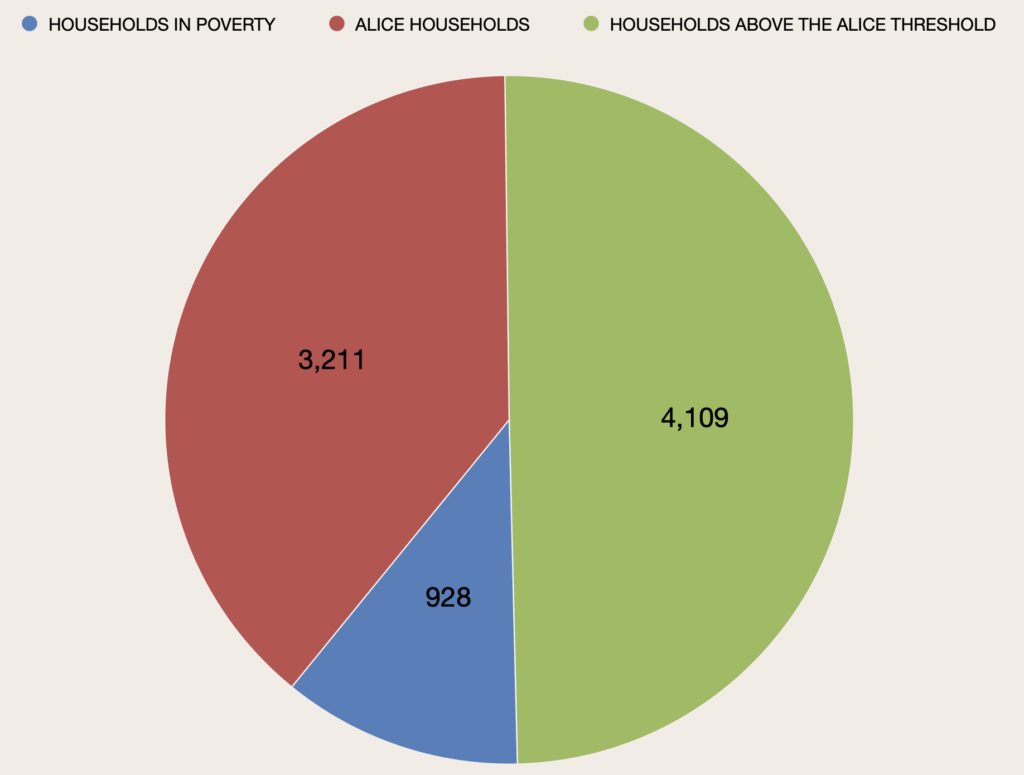

The report combines ALICE households with those earning below the Federal Poverty Level to arrive at the 50% number – about 11% of households in the area live below the poverty level, and 39% live above the official poverty line, but below a livable wage.

Households by Income

In the Florence, Mapleton, Dunes City area

The Federal Poverty Level (FPL) dates back to 1963 and President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Research at the time showed that American families spent about a third of their income on food. Roughly speaking, the government multiplied the cost of a basket of essential groceries by three to determine the poverty line.

It’s a formula that hasn’t changed very much over the past fifty years, even as the economic reality has shifted significantly.

Today, households spend a smaller percentage of their income on food, while housing and childcare have become the biggest costs for lower-income families.

The ALICE numbers, by contrast, are more comprehensive. The United Way study considers the cost of food, but also housing, education, childcare, healthcare, taxes, etc.

A family with children will have different costs than a retired couple or a single adult. “That’s really the genius behind the ALICE measures. It’s trying to take into account that full family budget that people are trying to juggle,” Mark Edwards said. Ewards is a professor of sociology and the director of the OSU Policy Analysis Lab, in the School of Public Policy at Oregon State University. He is also a member of the Advisory Committee for the ALICE Report in Oregon.

In Lane County, in 2023, the report identified the survival budget for a family of four, with two school-age children, as $76,356. The Federal Poverty Level was $30,000. As Edwards pointed out, the ALICE calculations are complex and are based on a variety of assumptions. But he believes the research is thorough and the methodology is clear. “What I like about the ALICE measures is that ‘here’s what we did. You can go back and look at the data. You can see how we did it. You can decide if you like our assumptions,’” he said.

The numbers change depending on the circumstances. No children in a household means a lower threshold. Kids in daycare? The cost goes up. People over 65 have their own added costs, including medical expenses. The ALICE report reflects that, as it tries to paint a picture of the actual cost of living in a community.

“One of the things that I think is also really valuable about it is the effort to try to drill down more locally, trying to take into account what’s going on on the ground,” Edwards said during an interview in 2024. By raising these questions across the range of financial costs, “it’s the beginning of a conversation,” Edwards said.

SHANA

After the fire, in search of a fresh start, Simpson used her remaining savings and moved with her sons to North Carolina. She wanted a lower cost of living, a lower crime rate and good schools for her boys. All signs pointed to Chapel Hill, North Carolina. “So without knowing anyone on the other side of the country, I just decided that we were going to do that,” she said.

They spent three weeks driving cross-country, visiting 23 states, turning the move into an adventure.

At first, North Carolina was good for all three of them. “We did really well. We had a beautiful townhouse,” Simpson said. Her boys would graduate from high school and eventually meet their fiancés.

Simpson cobbled together a series of jobs. She worked as a veterinary nurse, started a dog care business, a car detailing business and worked in an Amazon warehouse. At the peak, she said, she earned around $80,000 a year.

But a relationship turned abusive, and that led to anxiety and depression. The physical and mental health issues forced her to stop working. And so, Simpson decided to move again. She left her sons in North Carolina and returned to Oregon. Her father, a retired commercial fisherman, lived in Florence, and Simpson’s mom and brother lived in Eugene. She moved to Florence in September 2024 to care for her dad and start again.

Simpson would spend two months living in her car while she found a job at Safeway and then found an apartment in town. Her rent is $1295 a month, “plus electric and car insurance and all the other bills that come with being an adult,” she said.

Over the past few months, she said her hours at Safeway have been reduced. She is back to asking for financial help from Siuslaw Outreach Services, a local nonprofit that serves people in need, and is a regular at Florence Food Share. Her electricity has been shut off twice when she was unable to pay the bill. According to the ALICE report, 57% of cashiers in Oregon do not earn a sustainable income.

From January until the end of March, she was unable to afford her medication, including meds for treating the anxiety and depression she suffers from, made worse by the financial insecurity that meant she couldn’t afford the very medication she needed. Her car insurance lapsed. And Simpson said she received an eviction notice in May when she was unable to pay the rent.

She is looking for a new, better-paying job that can offer her more hours. Her father, because of his poor health, moved in with her. She has built a community at Florence Christian Church. She is training at Western Lane Fire and EMS Authority with their crisis response team. “Working with Crisis Response is one of the most special things I’ve ever gotten to do in my life.” “I literally feel like this opportunity is a gift to help,” she said.

Life is complicated. But a lack of money makes everything more difficult.

“It felt great in the past to be able to afford to pay my bills and make sure everything was paid on time and to have money to buy groceries, and to buy necessities or to take a drive to Eugene to see my brother. You know, to be able to afford things. It felt great.”

“Not being able to pay bills, I feel like I have no purpose. I have no value. I feel worthless. I feel like, I don’t know, I just feel like garbage. It just feels really terrible.”

“It is scary that everything I worked for and still work for could be gone. But also that it doesn’t have any meaning or purpose. Because I have nothing to show for it. And that’s what it feels like,” Simpson said.

ALICE

The ALICE report is a complex set of numbers and spreadsheets and charts. It labels, classifies and puts a number to financial struggle. It describes those in the middle: Not the poorest in our community, but those who struggle nonetheless. “What this ALICE research is doing is shedding light on a population that has gone unseen for so many years,” Angela French said. French is the director of marketing for the United Ways of the Pacific Northwest.

It also has the potential risk of pitting the very poor against the “working poor.” We can be quick to judge people who are not working, who live in their car, or on the street. Simpson’s story is the visible reminder of how thin and tenuous the line can be. One crisis can push a household beyond that line, and one decent job or opportunity pulls in the other direction.

The report is also designed to raise awareness. “Helping people understand the data is number one,” Noreen Dunnels, the president and CEO of United Way of Lane County, said in an interview last year. She shares the data with state and county leaders, people with the decision-making power to make change, she said.

Professor Edwards sees another purpose. Empathy. The rural experience is different from living in Eugene or Portland. Families with young children have different financial worries and needs than families with school-age kids or retirees living on a fixed income or a single person living alone. “That’s another benefit of this. A chance to see this is what young families might be experiencing in your community. Or it points out, this is what older folks in your community might feel,” Edwards said.

Any talk of a fix or solution is complicated, he said. “People just have such different views on how you achieve thriving communities and prosperity for a larger number of people.” Should government spend more of its limited resources on helping people or should it “try harder to free up the economy, to create better-paying jobs,” he asked.

The data of the ALICE report allows for a discussion. “If you’re sitting in your retirement home on the golf course in Bandon, it’s pretty hard to be imagining what kind of life people are living who just served your lunch there in the clubhouse,” Edwards said.

“If empathy translates into action, whether it’s people’s volunteering, or people voting or running for office, I do think that’s an important thing we did accomplish.”

Thank you for such a thoughtful explanation of ALICE and our “working poor”. So many in our community try yet cannot get ahead. Increased understanding will hopefully leading to increased empathy and support of this growing segment of our community.

Thank you, Will, for researching and sharing this story of life in our community. The ALICE data is eye-opening.