The Dry Time of Year

Oregon is in a drought. April through July was one of the driest on record. But so far, Lane County’s coast has seen little impact. The long-term outlook is a bit more cloudy, though unfortunately, not literally.

Written and photographed

by Will Yurman

Editor’s Note: As I write this, rain is in the forecast for Friday and Saturday. Good news for all of us. Whether it’s enough to relieve the drought conditions will probably depend on whether it’s a singular event or a sign of a change in the August weather pattern.

A plumber crawled out from under Mike Bones’ house last week. The water was still leaking. Bones lives on Route 101 north of Florence, where he runs Bones Nursery. The two talked about the leaks in the multiple pipes that supply water to the house and the garden nursery.

The plumber had managed to get the water running to the house. When Bones’ wife called out from inside the home, asking if she could do laundry, Bones was able to say yes. They could shower, flush, all the things.

But still no water for the garden.

Some of his potted plants were beginning to wilt in the dry August air, which followed the unusually dry April through July along the coast and much of the state.

“In the wintertime, Mother Nature does it all. But in the summer, things in a pot have to be watered,” Bones said.

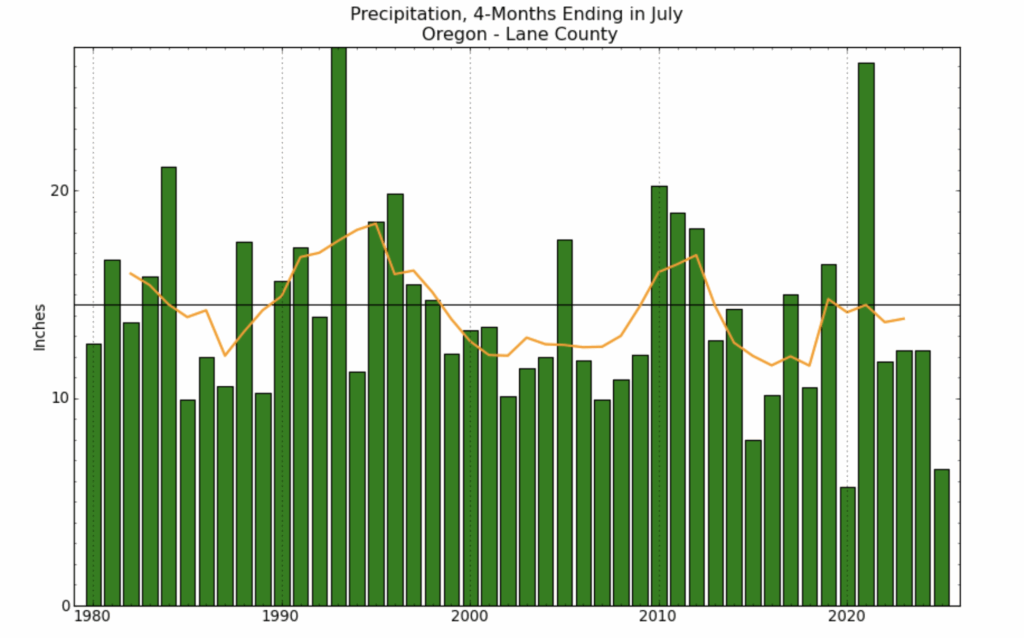

The last few months have been the fourth or fifth driest spring on record, according to Larry O’Neill, state climatologist and professor at Oregon State University. All of Lane County is in a drought, as is much of Oregon.

The governor declared drought conditions for Lincoln County in July. And nearly every water district in that coastal county has asked residents to conserve water.

But Lane County’s coastal community is more fortunate.

The short answer. We have lots of water. We have a reliable electricity supply. Wildfire risk is lowish, at least compared to the rest of the state. It’s good to be on our coast.

As long as you don’t think too far down the road, Bobby McFerrin has our number: “Don’t worry, be happy.”

WATER

For most of Lane County’s coastal community, water supply won’t be an issue this year. Florence draws its water from an underground aquifer. Mapleton relies on Berkshire Creek, and the Heceta Water People’s Utility District uses water from Clear Lake.

Florence

Florence’s water comes from the North Florence Dunal Aquifer. Thirteen wells pull water that supplies the nearly 10,000 residents of Florence, as well as businesses and visitors.

During the summer, the city uses about 1.9 million gallons of water each day. That drops off to about 700,000 gallons in the winter, according to Matt Hiatt, with the city of Florence’s Department of Public Works. Most of the increase in the summer is due to irrigation, Hiatt said.

Mike Miller, director of the Public Works Department, said the aquifer levels can drop after a dry spring and summer, but they recharge during a typical wet winter. The process is slow, making the aquifer a resilient source of water. A drop of water that lands at Collard Lake would take years to drain out to the Siuslaw River. “We’re very blessed that we are utilizing the groundwater,” Miller said.

Heceta

The Heceta Water People’s Utility District wouldn’t speak on the record. A look at their website shows they use Clear Lake to supply water to their roughly 4500 customers. The district has not imposed any restrictions and appears confident in its supply.

Mapleton

The Mapleton Water District serves about 500 people. It draws its water from Berkshire Creek, which feeds into the Siuslaw River. Creek levels do drop during the summer, especially a dry one. The lowest levels are typically in the second half of August.

Mapleton has an aging water system that has created problems for the district. But the current water supply is good, Matthew Ferkey, the district’s lead water operator, said.

Lower water levels are to be expected. “During the summer, our water flow is normally low, so we anticipate that,” office administrator Jordan Walker said.

But a low creek level does shrink the safety net. A leak in the system, combined with low creek levels, could potentially cause problems for the district.

Private Sources

Many on the coast outside of the three water districts rely on private wells or springs. Clare Brien lives in West Lake and has a spring on her property. She hasn’t noticed a decline this year, and it’s never run dry – though they are careful about how much water they use.

Annie Schmidt lives on Glenada Road and has what she described as an “extremely low-flowing well.” She relies on the discipline to conserve water and two 800-gallon tanks that hold her well water. When she has guests, she tells them to take five-minute showers. She hasn’t noticed a difference this year either.

ELECTRICITY

Central Lincoln provides electricity to almost everyone along Lane County’s coast. That represents about 13,000 meters – including residential and business customers. Central Lincoln purchases all of its power from the Bonneville Power Administration. About 85% of the electricity comes from hydropower, primarily from the Columbia River.

Central Lincoln wrote in an email that the company has no concerns about the energy supply in 2025 and that prices are expected to remain stable. “Current drought conditions will not have an immediate impact on customer rates. Central Lincoln does not charge variable pricing, so our customers pay a consistent flat rate for electricity throughout the fiscal year.”

But lower water levels mean the dams produce less electricity. Levels on the Columbia River Grand Coulee Dam are well below their 30-year average, though a bit higher than last year’s record low. Long-term, that could require the use of more expensive sources for energy, which would mean customers could pay higher electricity prices down the road.

FIRE

We are surrounded by forest, so we are not immune to the risk of wildfires. But those risks are lower for the Siuslaw Forest than for other forests in Oregon.

A U.S. Forest Service press release from August 5, 2025, for the Pacific Northwest made that point: “Fire danger levels on all National Forests, except the Siuslaw National Forest, are High to Extreme.”

The drier weather increases the risk of wildfires, but it is humans who create the greatest threat, Adam Veale said. Veale, the Deputy Interagency Fire Staff Officer for the Northwest Oregon Interagency Fire Management office, said that all 16 fires in the Siuslaw National Forest this year (as of August 11) were human-caused. A 17th fire was reported shortly after we spoke, and he said it appeared to be human-caused as well.

Plants are not equal when it comes to fire risk. The forest service uses a scale based on how long it takes material to dry. “We have one-hour fuels, ten-hour fuels, a thousand-hour fuels,” Veale said. Grasses dry out quickly; they are a one-hour fuel. An hour of hot sun can turn them into fuel for a fire. A wet old-growth log can hold its moisture for 10,000 hours. Smaller trees and branches fall in between.

Our wet winters can protect the largest trees through a dry summer, but not so for grass, brush, and smaller logs and branches. Coastal fires tend to happen when multiple factors align. Dry weather, low humidity and high winds are the triple threat of wildfires.

“The last time I saw a fire of any genuine concern [on the Oregon Coast] was in 2020 outside of Lincoln City, during the big wind event,” Veale said.

The Echo Mountain Fire burned 2,500 acres and destroyed hundreds of homes in September 2020. It was fed by high temperatures, winds, and dry conditions.

Oregon State Climatologist Larry O’Neill compared this year to 2020, the last very dry spring. “The very large wildfires had two things in common. One was that they occurred after a very dry spring and summer, and the second was when we had a strong east wind event.” We’re not out of the woods until we get a heavy “wetting rain,” he said. Those rains typically happen in mid-September.

The biggest risk of fire is people, Veale said. Dry weather racks the pool balls, but humans take the break.

LONG TERM

The short-term outlook for Florence, Mapleton, Dunes City and the surrounding areas is good. More dry weather into August gives us all a last chance to enjoy the sunshine before the inevitable march towards winter’s rain. But unlike other communities in Oregon, we should have plenty of water, and with some good luck and responsible outdoor behavior, we will avoid a significant fire.

But that doesn’t change the future. Long-range forecasts are for drier and warmer weather. Less rainfall is predicted for our summers, and higher temperatures mean faster evaporation, which would create more of that one-hour, 10-hour, or even 1000-hour fuel for fires.

Climate change forecasts are predictions, not guarantees, but Professor Erica Fleishman says the science is sound. An occasional drought might not be a problem. Natural systems will generally bounce back, they are resilient, she said. But the research says it will become warmer and drier, increasing the likelihood of more frequent droughts that can stress an ecosystem. Fleishman is a professor at Oregon State University and director of the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute.

On top of that, “many natural systems are already stressed because they’re smaller and they’re more fragmented. And there’s a lot of human influences on them,” Fleishman said. More people put a greater demand on the system, and by definition, put more people at risk.

The impact on our water supply is less clear. But less rain and warmer weather could impact creek levels, or even lake and aquifer levels.

“Aquifers recharge over long periods. You’re not going to deplete an aquifer in one drought year. But the collective demand on aquifers is increasing, and they recharge slowly,” Fleishman said. “I wouldn’t be sanguine about the aquifers.”

And it is worth remembering that we do not live in isolation. The coast is a place of moderate temperatures and plentiful rainfall. But our electricity comes from the Columbia River. Our visitors come from hot, dry places. People move here to escape the heat. Insects and plants invade as the weather changes. It is complicated and all connected.

O’Neill thinks back to 2023. He was monitoring droughts, writing reports. It can be hard work. “Drought monitoring is really difficult, and it’s really hard to see people suffer from it. Especially farmers,” he said.

It was August. And there was a rare storm. “We had like an inch or two of rain in Eugene.” He remembers walking outside that night, sitting and listening to the sound of the rain on his roof and realizing how out of place that sound was in August, and how much help it would mean for farmers and others affected by the drought. “It was just really nice to hear that.”